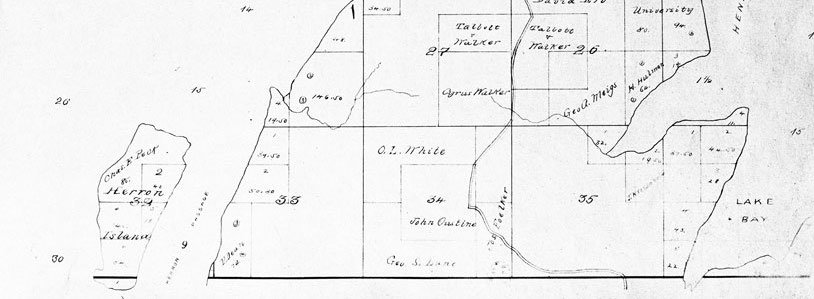

An 1889 map showing Charles E. Pack (misspelled as Peck) as the owner of a portion of Herron Island. From Plummer's Complete Atlas of the County of Pierce, Wash. Courtesy Tacoma Public Library

An 1889 map showing Charles E. Pack (misspelled as Peck) as the owner of a portion of Herron Island. From Plummer's Complete Atlas of the County of Pierce, Wash. Courtesy Tacoma Public Library

This article has been revised to reflect new information..

There’s nothing like reconstructing a forgotten life from the past. Bit by painstaking bit, a story slowly emerges, sometimes seemingly out of thin air, and soon we can’t tear ourselves away. A life hums with echoes of its time; listen closely to someone’s story and you’ll hear the voice of their age.

Take for example the story of Charles Emil Pack.

Researching the history of Herron Island required identifying the island’s first white settlers. None of the standard reference works on KP history mentioned their names, so it was time to consult original sources.

The first settlers would have been granted patents to the land by the Government Land Office in Olympia, the agency in the Department of Interior responsible for surveying and managing lands that had come into the public domain.

GLO records have been digitized and are available on the Bureau of Land Management’s website, the GLO’s successor agency. Survey maps for Case Inlet provided the coordinates assigned to the island when the area was first surveyed in 1853 and 1856.

Entering those coordinates on the GLO site returned three hits.

The earliest settler was a Charles Emil Pack, who had claimed a total of 92 acres along the north and west sides of the island in 1872. Over 20 years later, in 1894, a patent for most of the rest of the island, about 160 acres, was issued to a Julius Sunde. Finally, in 1895, the narrow strip of land on a high bank at the south end was deeded to the Northern Pacific Railroad Co., part of the land grant authorized by Congress in 1864 to help finance construction of that railroad from the Great Lakes to Puget Sound.

A treasure trove of information existed on Julius Sunde, but Charles was more elusive and harder to track down. Julius led a rich social and professional life, with frequent mentions not just in government records but also in newspapers, magazines, books and letters.

By contrast, Charles Pack, Charley to his friends, left only a few scattered traces. Those few pieces of the puzzle put together, however, were enough to outline the trajectory of his life.

Charles Emil Pack was born in Basel-Stadt canton in German-speaking Switzerland in 1829. He emigrated to the United States, arriving in New Orleans in April 1847 on the 900-ton, three-masted ship Taglioni, which made regular runs between Le Havre in France and Louisiana. One hundred and seventy of the 199 passengers listed on the ship’s passenger manifest, including 17-year-old Emil (the name spelled Emile by the ship's officer), gave their occupations as farmers and stated they were headed to Missouri. Young, expanding America needed farmers; Europe heeded the call. The 1880 territorial census shows Charley as the only inhabitant on Herron Island.

Emil’s plans seemed to change, however. The war that broke out in 1846 between the United States and Mexico following the U.S. annexation of Texas was in its second year and volunteers were needed. Within a few days after he got off the Taglioni, Emil joined Company B as a private in the newly formed Battalion of Louisiana Volunteers. History does not record when he was discharged, but the war ended Feb. 3, 1848. Emil’s service during that war would be recognized four decades later; in 1887 Congress authorized pensions for survivors of the Mexican War who were over the age of 62. Emil applied in 1891 and was granted a monthly pension of $8 starting in 1893.

In 1855 Emil surfaces again, this time in New York City, where he applied and was naturalized as a U.S. citizen. His name on the naturalization certificate is still Emil; the name Charles would not appear until later.

Fast forward to 1871, when Emil, by now Charles Emil, has moved to Washington Territory and is sharing a house on a farm in Mason County, west of Herron Island across Case Inlet. The territorial census shows 326 inhabitants in the county, not counting Indians. Perhaps that was too crowded for Charley; in September 1872 he applied for a patent on 92 acres around the northwest part of the island. According to his statement, he had been living there since January of 1872, in effect squatting on public land. The federal Land Act of 1820 allowed the sale of public lands at $1.25 an acre; because the parcel was near land deeded to the Northern Pacific Railroad the sale price was $2.50 an acre, a rate set by Congress so as not undercut sales of railroad land. Charley paid a total of $230, about $5,000 in today’s money.

The purchase was approved on July 25, 1873, making 43-year-old Charles Emil Pack the first documented settler on Herron Island.

Charley cleared two acres and built a chicken coop and an 18-by-20 foot house, “a comfortable house to live in,” according to the statements of two witnesses, his friends Joseph Sherwood and John Wisman, provided in support of his claim.

The 1880 territorial census shows Charley as the only inhabitant on Herron Island. In that year’s agricultural census, he is listed as a subsistence farmer; the census enumerator comments that Charley “has cleared a small patch round the shanty, and raises enough for his own wants, selling nothing.”

We do not know when Charley left the island. In 1895, two years after his Mexican War pension was approved, he deeded his land to Allen Fish, the new postmaster at the village of Herron on the mainland who was to serve until 1904. Fish leased back to Charley his cabin and five acres adjacent, for Charley to use for the remainder of his "natural days." According to the lease, which was recorded with the county, Charley's cabin was on the east side of a small bay at the northwest end of the island.

Charley died on June 7, 1898, at the Fannie C. Paddock Hospital in Tacoma at the age of 68. On his death certificate his occupation is given as cook; his farming days on the island had probably been over for some time. He is buried at the Old Tacoma Cemetery in Tacoma.

Charley Pack never married and appears to have lived a solitary life. His shanty did not survive subsequent logging and development on the island, but the best area to farm would have been the sunny slope on the island’s west facing side. Charlie Sehmel, who logged the island in the 1950s, remembers several gnarly old apple trees on the west side. Apple trees can live several decades; it’s possible those were planted by Charley Pack, Herron Island pioneer.

Joseph Pentheroudakis is writing a book on the history of Herron Island.

UNDERWRITTEN BY THE FUND FOR NONPROFIT NEWS (NEWSMATCH) AT THE MIAMI FOUNDATION, THE ANGEL GUILD, ADVERTISERS, DONORS AND PEOPLE WHO SUPPORT INDEPENDENT, NONPROFIT LOCAL NEWS