“The attack on the Fascist redoubt which had been called off on the previous occasion was to be carried out tonight. I oiled my 10 Mexican cartridges, dirtied my bayonet (the things give your position away if they flash too much), and packed up a hunk of bread, three inches of chorizo, and a cigar which my wife had sent from Barcelona and which I had been hoarding for a long time.”

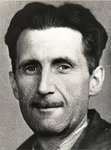

That is George Orwell, then 34, in the mountains of Aragón in northeast Spain in January 1937, preparing to slip out of his trench after dark, cross no man’s land, and climb a ravine to capture an enemy machine gun nest.

Five months later he was on the run from the secret police, recovering from a gunshot wound to the neck that destroyed a vocal cord and paralyzed his right arm, and hiding in the ruins of bombed buildings in Barcelona while trying to rendezvous with his wife and flee the country.

It was all very inconvenient.

“The worst about being wanted by the police in a town like Barcelona is that everything opens so late. When you sleep out of doors you always wake up about dawn, and none of the Barcelona cafés open much before nine. It was hours before I could get a cup of coffee or a shave.”

In July 1936, General Francisco Franco and other elements of the Spanish national military launched a coup against a squabbling leftist Republican government weakened by division. The Nationalists were supported with money, weapons and troops by Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy. The Republicans were backed by the Soviet Union and Mexico. The other great powers did little, in Orwell’s view, having no love for Communists or understanding of Fascists.

Orwell was a former Imperial Police Officer in Burma (from where we have his famous essays about colonialism, “Shooting an Elephant” and “A Hanging”), and was about to publish his fifth book (“1984” and “Animal Farm” were still years away). His Labor Party sympathies, military experience and journalist’s curiosity took him to Spain, where he joined one of the few Republican militias that considered him sufficiently radical to be trusted.

“I had accepted the (newspaper) version of the war as the defense of civilization against a maniacal outbreak of Colonel Blimps in the pay of Hitler. ... Since 1930 the Fascists had won all the victories; it was time they got a beating, it hardly mattered from whom.”

The soldiers in his unit were farm boys aged 12 to 20, mostly refugees from Fascist territory who had never held a firearm in their lives. Orwell, appalled at their deprivation and concerned for their well-being, was rapidly promoted from private to brevet lieutenant and struggled to keep his charges safe from the enemy, the elements, and themselves. Their rifles were over 40 years old (in other words, from the 19th century) and without meticulous care were likely to fire the bolt back into the shooter’s face. Orwell called their hand grenades “impartial Anarchist bombs” because one might kill the man who threw it as readily as the man it was thrown at.

Orwell’s perception of the government’s apparent disinterest in men and matériel matured as he pursued it. Foreign supplies were indeed coming into the country but were sent to pro-Soviet forces or cached to keep them out of the hands of potential rivals, like his militia.

That deliberate neglect doomed the Republic. Orwell explains why in two chapters of exposition describing “the kaleidoscope of political parties and trade unions, with their tiresome names,” which he gamely invites readers to skip if it seems tedious. “Compared with the huge miseries of civil war, this kind of internecine squabble between parties, with its inevitable injustices and false accusations, may appear trivial ... (but) I believe that libels and press-campaigns of this kind, and the habits of mind they indicate, are capable of doing the most deadly damage.”

Orwell was invalided out of the front after being shot through the neck by a sniper, and returned to Barcelona. His wife, Eileen, met him in the lobby of her hotel to casually inform him the government had declared his militia enemies of the state and that he must run at once before the desk clerk spotted him.

As their friends disappeared into government dungeons, Orwell sought out one ruined building after another to hide in while Eileen, under constant surveillance, appealed to the British embassy and government officials. Their names were on a list of “foreign agents” marked for arrest, but because of the confusion of war “in the end we crossed the frontier without incident. ... Two detectives came round the train taking the names of foreigners, but when they saw us in the dining car they seemed satisfied we were respectable.” Even after such a narrow escape, they were sorry to leave Spain, still wanting to share her troubles and her joys.

More than 500,000 people were killed during the 1936 to 1939 war. Over 100,000 people remain missing. Unmarked mass graves are found to this day in Aragón.

Back in London by summer, Orwell published this memoir in less than seven months, before the end of that war and before the beginning of the next, hoping to rouse his countrymen from “the deep, deep sleep of England from which I sometimes fear that we shall never wake till we are jerked out of it by the roar of bombs.”

UNDERWRITTEN BY THE FUND FOR NONPROFIT NEWS (NEWSMATCH) AT THE MIAMI FOUNDATION, THE ANGEL GUILD, ADVERTISERS, DONORS AND PEOPLE WHO SUPPORT INDEPENDENT, NONPROFIT LOCAL NEWS