It seems an appropriate season to revisit the work of an author who wanted nothing but that his readers recognize the unexpected grace in people unlike themselves and offer them an unfamiliar mercy.

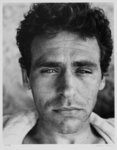

A commercial disaster when it was published, “Let Us Now Praise Famous Men” is considered one of the greatest American nonfiction works of the 20th century. James Agee became the foremost film critic of his day and wrote a couple of famous screenplays before succumbing to the effects of alcoholism in 1955 when he was 45. His novel “A Death in the Family” earned him a posthumous Pulitzer Prize in 1958.

I read “Let Us Now” the first time when I was 26 (the age of the author when he started writing it) and found it baffling and troubling. I sensed there was something missing — in me — that kept me from understanding.

This is no simple book, as Agee reminds us more than once, apologetically:

“For I must say to you, this is not a work of art or of entertainment, nor will I assume the obligations of the artist or entertainer, but it is a human effort which must require human co-operation.”

In other words, it is an ordeal.

Agee was teamed up with a Farm Security Administration photographer, Walker Evans, by Fortune magazine in the summer of 1936 to document the lives of three white sharecropper families in Alabama in what was supposed to be an exposé about the effect of the New Deal, if any, on Southern poverty during the Great Depression.

Fortune got more than it bargained for: tens of thousands of words more. Agee refused to change anything and shopped the manuscript around to one publishing house after another until it was finally printed in 1941. It sold 600 copies and was remaindered.

Here is the problem: Agee suspects we are unworthy of reading his book, just as he suspects himself unworthy of writing it. He does not allow us to meet a single member of his families until a third of the way through, after we have overcome barricades of exposition, prose poetry, outlines of expectations, and his repeated challenges to go no further if we don’t like what we’ve seen so far.

He tests us in this initiation ritual to ensure we are not there to “pry intimately into the lives of an undefended and appallingly damaged group of human beings,” and, more to the point, to transform us into something more than we are, as all good rituals do.

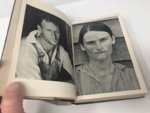

Only then does Agee begin to crack open the furnace of his forge to engulf us in searing portraits of people, places and moments in single paragraphs or even sentences that go on for pages. One gets a taste of what’s to come looking at the faces in Walker’s photographs at the beginning of the book, people who stare up from these pages with a mixture of resentment, longing and pride.

We are made to relive Agee’s humiliation when a landlord farm owner stops the car he’s riding in to call his tenants from his field to perform a traditional spiritual for his guests. The men, women and children stare straight ahead, and sing.

“None of these people has any sense, nor any initiative,” says the landowner. “If they did, they wouldn’t be farming on shares.”

The landowners acquired their property buying up farms as they were foreclosed in the 1920s and ’30s. When a farmer agreed to work for shares, they became an employee of the landowner and ineligible for any relief under the New Deal.

“Tell you the honest truth, they owe us a big debt,” says another. “Now you just tell me, if you can, what would all those folks be doing if it wasn’t for us?”

Agee describes the farm houses rented from the landowners they serve with the empirical intensity of a scientist desperate to understand what he observes. He inventories the contents of rooms, shelves and drawers, down to the odors, and analyzes how chairs, trunks and trinkets are arranged because "this kind of spacing gives each object a full strength it would not otherwise have” and can tell us much about the hope, or lack of it, in the families who own them.

As a journalist, Agee can explain the competing qualities and prices of cotton seed, mules and men in a few sentences, but will take 14 pages to describe the unspoken impact of a thunderstorm on a family huddling in their rented shack as water streams through the roof at the end of a cruel drought: “I have no right here, much as I want it, and could never earn it, and should I write of it, must defend it against my kind.”

He describes parting from a 16-year-old girl, already married two years to a man older than her father. She’s run twice but is being returned to the man, now working on a more distant plantation so she can’t get away again so easily:

“The very most I could do was not show all I cared for her and what she was saying, and not to even try to do, or to indicate the good I wished I might do her and was so utterly helpless to do.”

Agee was born in Tennessee in 1910 and though he wasn’t rich, he was privileged, and his talent took him far. He could not resist embracing people close to his own country and tried to prove with this work our need to do the same. The trouble came as he discovered how big a job that was.

UNDERWRITTEN BY THE FUND FOR NONPROFIT NEWS (NEWSMATCH) AT THE MIAMI FOUNDATION, THE ANGEL GUILD, ADVERTISERS, DONORS AND PEOPLE WHO SUPPORT INDEPENDENT, NONPROFIT LOCAL NEWS