A school year unlike any other is upon us, fresh on the heels of two other school years unlike any others. Students are returning to their posts while administrators rearrange deck chairs and teachers watch for icebergs. Volunteers like me fill in the gaps, playing blackjack in the hall with first graders who hate math.

We are still grappling with what the pandemic, politics and polarization have done to us, including the classroom. How are we to steer this ship through these new problems while the old ones persist?

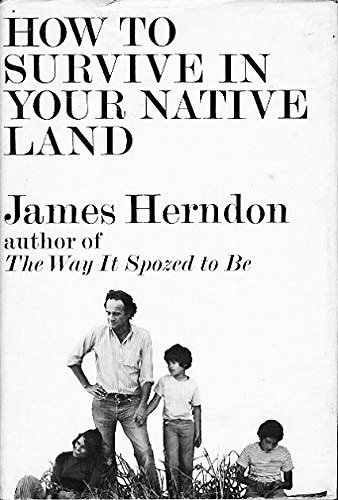

James Herndon addressed the same question in 1971 in his memoir after teaching in San Francisco’s public schools for 10 years in the 1960s, one of the most turbulent decades in American history.

He starts his answer, and his book, with the kind of resigned admiration instantly recognizable to any teacher: “I might as well begin with Piston.”

Piston was this screwup eighth grader who roamed the halls, smoked in the bathrooms, and gave the finger to the kids in Egypt class every day. Then he got stuck in this experimental classroom where the students determined what they were going to learn. It was so boring, there was nothing to do. Then some kid decided she wanted to build a kite, and then all the kids started building kites. Piston refused because Piston didn’t do what everyone else did because everyone hated Piston.

After all the other kids spent a week building their kites and decorating them and flying them while the kids stuck in Egypt class got jealous and gave them the finger through the windows, Piston started to build his kite. It was 20 feet long and made of heavy 1-by-2 lumber and yards of butcher paper he decorated with painted monsters. The teachers congratulated themselves on successfully engaging Piston in something, anything, other than giving the finger to Egypt class and smoking in the bathrooms. It wasn’t like this thing could ever fly, but it was proof they’d managed to connect with this screwup kid the whole school hated.

Then Piston somehow organized a bunch of kids to help him take the kite outside. He tied a clothesline to it, and they ran across the playground hoisting it over their heads until the thing took off.

“It was terrifying — plunging and wheeling and lurching through the thin air, a ton of boards and heavy paper and ghouls and toothy vampires leering down at an amazed lunchtime populace. ‘Jesus Christ, look out!’ yelled (the principal) just as the giant came hurtling down like a dead flying mountain ... When it crashed, everyone was seized with a madness and rushed to the kite, jumped on it, stomped it, tore it, murdered it (except the teachers, and we wanted to), and when it was over and the principal had everyone pulled off the scattered corpse of the kite and sitting down on benches and shut up there was nothing left of it but bits and pieces of painted butcher paper and 1-by-2 boards and clothesline rope.”

And there was Piston. “It flew, man,” he said.

Herndon started teaching when he was in his mid-30s after serving as a merchant marine in World War II and years living abroad. “Briefly, I had the idea that America needed me... Certainly I would be welcome as a teacher, if only as an antidote to the kinds of teachers I had known as a child.”

He was fired from his first job for poor classroom management, then went on to become one of America’s most influential writers on education.

When his own child developed what seemed to be a minor health problem that became overwhelming, Herndon began to see his students in a new way.

He and his teaching partner, Frank, decided to embark on a “voyage to the New World,” by assembling students of different abilities and outlooks and ages into a single experimental classroom where the kids would drive the curriculum. But the New World is by definition unknown territory, and the teachers and kids careen from boredom to exuberance to despair as they try to stay on the voyage by doing things the school doesn’t like while also meeting district standards.

Toward the end of the year. Herndon describes a meeting where one of his screwup kids is going to be expelled, and he and Frank are all for it.

“One day the roof finally fell in on Greg and he reaped the rewards of his f...... around all year. The counselors, taking note of all his F’s and ‘Unsatisfactories for Citizenship,’ sent out forms to his teachers, asking them to comment. Of course they all wrote that he was no damn good. There in the office, hearing all the teachers tell Greg’s parents that he wouldn’t do spelling, wouldn’t do science, wouldn’t do this and that (wouldn’t even do Shop, for Christ’s sake!), in the face of all those helpful, frowning adults, Frank and I suddenly saw that Greg was really OK... We remembered that he was usually around when something really needed to be done — in short, we all of a sudden realized that he was a pretty helpful, alert, responsible kid, and we said so. Everyone was astonished. Could he spell? Did he do Egypt? Did he make bookends? We left realizing that we had just realized that this f...-up kid who drove us crazy was really OK and that, far from the class being better if he was gotten rid of, he was actually needed... Frank and I came out of the meeting looking at each other strangely, wondering what had happened to us.”

Professionals call that a teachable moment. Or maybe recognizing your native land for the first time. Perhaps that’s how we find our way back there.

UNDERWRITTEN BY THE FUND FOR NONPROFIT NEWS (NEWSMATCH) AT THE MIAMI FOUNDATION, THE ANGEL GUILD, ADVERTISERS, DONORS AND PEOPLE WHO SUPPORT INDEPENDENT, NONPROFIT LOCAL NEWS