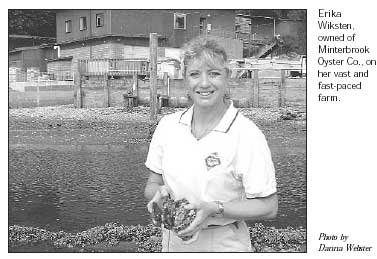

She is a farmer’s daughter. Erika Wiksten’s father was lured into oyster farming at age 23. Harold Wiksten’s aquatic farming business stayed in the family when Erika became the owner of Minterbrook Oyster Co. in 2002, and now she’s in the process of bringing her father’s 1954 business into the 21st century.

She is a farmer’s daughter. Erika Wiksten’s father was lured into oyster farming at age 23. Harold Wiksten’s aquatic farming business stayed in the family when Erika became the owner of Minterbrook Oyster Co. in 2002, and now she’s in the process of bringing her father’s 1954 business into the 21st century.

She and her management team call their vision “One World, One Life,” an important theme to all her business practices. Caring for the environment is her top priority.

This July morning started, as usual, around 5:30 a.m. Wiksten drove her truck to Rocky Bay, loaded up 25-pound bags of clams, and brought them back to the plant for today’s preparation.

The drive into Minterbrook winds down a long paved lane lined with trees and grassy yards. The deer and other wild life have grown accustomed to the farmer’s presence. An otter scurries out from under the office porch steps as Wiksten and her three canine partners open up for business. First thing this morning, she coordinates a meeting location for a truck driver and the boat captain at Hartstine Island. Then she goes about checking the cooler temperatures, starting the ice machine, and arranging to have a truck moved to the loading area for the first deliveries to Seattle.

By 7 she is at her desk, in a spacious office that was the children’s play area back in the days when her father was in charge. His office was down a few steps. He had couches and antique nautical furnishings, more like a living room than the efficient computer desks of today.

Wiksten calls the health department and checks emails. When a broker for her newest product idea drops in, she clears her schedule to talk with him.

Dave Laundry, who started work for Minterbrook 15 years ago, takes a visitor on a plant tour. He was foreman for Harold Wiksten and now is the hatchery manager. He starts where the dump trucks bring loads of dry shells to a churning hopper. After a spin in the hopper, the shells are conveyed into a giant cement mixer that is the shell washing machine. This operation has been the same for 25 years, but new ideas for a washer and hopper combination are on the planning table.

The work is labor intensive. Truck drivers bring the loads and men are stationed along the process to keep the shells moving. The cleaned shells, bagged into nylon sleeves, are called cultch and used to set the seed. Seeded cultch are bundled into huge bales ready to plant in the bays. Last year they planted 42,000 bags. The seed tanks are the nurseries where oyster larva are released in a carefully controlled environment and encouraged to attach to the cultch.

The larva acquisition costs about $3,800 a week. Seven to 10 little specks can be seen on the shiny lining of some shells. Laundry says the larva swim with cilia until they attach to something. Once attached to their host, the mother shell, They lose their cilia and develop organs, like a stomach, necessary for feeding. At that stage they can digest algae. The larva stay in the nursery seed tanks for a week while the water temperature is adjusted from 73 degrees down to bay temperature. From the nursery they are taken to deep water holes. Laundry sends out 1,504 bags each week.

In six to eight months, the young oysters begin lifting up from the mother shell. The bags are taken to a beach, opened and the oyster clusters are spread. At Minter beach, about 40,000 bags cover each acre. When beachcombers take these clusters, they are kidnapping Laundry’s very precious babies.

By the time Laundry gets back to the office, Wiksten is ready for a beach walk. Walking on the beach is essential to this business.

“Most of it you have to go out and see for yourself,” she says. Technology can’t help with the majority of the work. “A lot of what we do —picking shells, breaking shells, spreading the seed, is done by hand,” she adds.

Minter Bay was once a polluted estuary. The reintroduction of oysters has brought it back to a healthy aquatic habitat, according to Wiksten. “The estuary is a true indicator of our environment as a whole. If an estuary is degraded, that impacts the whole eco-system,” she explains.

Wiksten wades through clear water as she hikes toward the sand spit. Shells crunched underfoot are on a path that doesn’t harm the oyster crop. Her father taught her, “Don’t walk on the oysters. Don’t walk on the seed.”

A blue heron poses on a large driftwood log. A gaggle of geese swim just off shore. “The birds do well, the fish do well,” she points out. These are signs of a recovering eco-system.

Little shacks that once lined the sand bar in the 1900s have washed away. The sand bar itself is eroding, but that’s a good thing. As the sand bar opens up it helps flush out the bay. There are no traces of the shacks, but carcasses of old sunken ships jut up from the sand.

Wiksten digs for surf clams. She finds a cockle and live sand-dollars. As a little girl, she experienced one of those childhood letdowns. She was told that sand-dollars were sea cookies. They are not good to eat. Later, she took some consolation from the fun of opening dead ones and finding five little birds. She says the popular sand-dollar is actually the locust of the shell-fish world. Where you find lots of sand-dollars, you won’t find an aquatic balance.

Little crabs and baby bullheads scurry out from underfoot at Minter Creek. These creatures were once inhabitants in the zoo that young Wiksten and her brother created for entertainment. They offered 25-cent tickets to their parents to visit.

Those early days and the water zoo are the inspiration for Wiksten’s biggest dream. She wants to establish an aquatic habitat facility for local schools, where students can learn about aquatic environments.

“Wouldn’t that be fun?” she asks. Fun is a word heard often on the walk. The work is fun, life is fun, the zoo dream is really fun. There is a bounce in her step, a smile on her face and her eyes are opened wide with expectation.

She wades around an oyster barge just before reaching shore. She points out its four-cycle engines and says all the fluids Minterbrook uses for trucks, boats and equipment are environmentally friendly. They use hydraulic fluids derived from vegetable oil and food grade lubricants on conveyer chains.

The last stop is the retail building. The place is fast paced. The men in the long line of shuckers come from several different countries. Many study English as a second language in classes provided at the farm. “Age, race and gender are not relevant. For one is judged by work ethic and heart…You are valued as an individual and not regarded as a number…You are part of the team, the family,” Wiksten wrote in her journal about the company.

She said her parents worked hard all their lives. They taught their kids a work ethic. After school, the kids worked. “You have to be grounded, never forget your roots,” she says. Wiksten knows first-hand all the farm’s jobs.

For Wiksten, the fun of work is in new creations. She shows off a knife designed by Minterbrook for the shuckers, jar labels in French, Spanish and English, colorful plastic lids with imprinted bar codes—a first in the industry—and the tamper-proof seal under the lids that took 26 tries to perfect. She offers some oysters to a visitor and gets a bag for her lunch as she drives to her next meeting.

When she returns, she calls the harvest crew to see how they did. “Some of my highest paid employees are the harvesters. Without them you wouldn’t have a product,” she says. After those calls, she sets tomorrow’s schedule, knowing the probability of keeping hers is poor. She will return phone messages and check email before she closes up, usually around 10 o’clock at night.

In the good old days, a farmer worked from dawn to dusk but this aquatic farmer works from dark to dark. Erika Wiksten does get to see the light of day. And she delights in the fun of her work. The call of eagles is her elevator music, and the hulking supervisor that keeps her under his scrutiny is called Mount Rainer.

How many people get to say, “It’s time to go to work” and then head for the beach? It’s all in a day’s work for the oyster farmer.

UNDERWRITTEN BY THE FUND FOR NONPROFIT NEWS (NEWSMATCH) AT THE MIAMI FOUNDATION, THE ANGEL GUILD, ADVERTISERS, DONORS AND PEOPLE WHO SUPPORT INDEPENDENT, NONPROFIT LOCAL NEWS