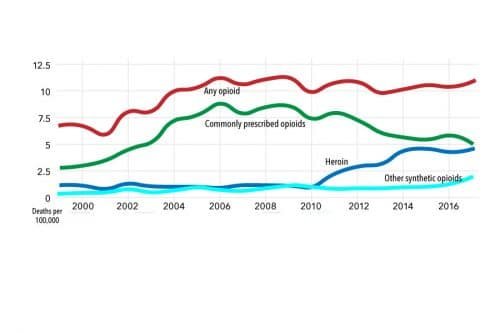

Washington statewide opioid death rates. Data sources WA State Dept of Health; Office of Financial Management

What is it?

The United States is experiencing an epidemic of drug overdose deaths, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Since 2002, the rate of overdose deaths across the nation has increased by 79 percent. Since 2000, deaths involving opioids have increased 200 percent.

Opioids are narcotics that produce morphine-like effects used for pain relief and anesthesia. They also affect the areas of the brain that control breathing. High doses, especially of fentanyl, can cause breathing to stop completely. Fentanyl is a powerful synthetic opioid similar to morphine but 50 to 100 times stronger.

Heroin is a type of opioid made from morphine, a natural substance that comes from opium poppy plants. Prescription pain relievers and heroin are chemically similar and produce similar effects. Some people who get addicted to opioid pain relievers switch to heroin because it’s cheaper and easier to get.

How did it start?

According to the Washington state attorney general’s office, painkillers such as OxyContin and Vicodin became popular in the 1990s in the belief there was little or no risk of addiction based on allegedly flawed or even falsified research and marketing. Treating pain became easier and a higher priority. As the number of prescriptions increased, so did rates of abuse, addiction and overdose.

Opioid prescriptions and related overdoses fell in Washington after 2011 when the Legislature and health care providers began to crack down and encourage use of non-opioid painkillers. But users turned to heroin, fentanyl, methamphetamines and benzodiazepine (an anti-anxiety medicine), and cheaper synthetic opioids, including imitation fentanyl, and overdose rates for those drugs increased, according to the state Department of Health.

Locally, pills called Mexi-blues are counterfeit OxyContin tablets laced with fentanyl or other synthetic opioids that cost about $30 each, according to the Pierce County Sheriff’s Department. The same drug can be taken orally, snorted, smoked or injected. A single dose can be fatal.

How bad is it?

Though the number of total opioid overdoses has fluctuated since 2006, in 2016, 694 Washingtonians died of opioid-related overdoses, according to the health department. (2016 is the most recent year for which comprehensive data is available.)

From 2002 to 2004, the state death rate just from heroin was 0.65 per 100,000 residents; from 2014 to 2016 the rate was 4.12, an increase of 634 percent. In Pierce County during the same time periods the rate increased by 385 percent.

Sen. Patty Murray recently released a report showing that the cost of the opioid epidemic in this state in 2016 was $9.2 billion. The National Institutes of Health estimated that every dollar spent on treating addictions saves four to seven dollars in reduced drug-related crime and criminal justice costs. When savings related to health care are included, total savings can exceed costs 12 to 1.

How is it being stopped?

Drug addiction is increasingly recognized in the medical community as a medical diagnosis rather than a moral failing. The NIH website notes: “Addiction is defined as a chronic, relapsing disorder characterized by compulsive drug seeking, continued use despite harmful consequences, and long-lasting changes in the brain. It is considered both a complex brain disorder and a mental illness.”

Drug overdose deaths fell last year in 14 states including Washington, according to the CDC, where aggressive approaches to addiction treatment have been implemented, including:

Washington statewide opioid death rates. Data sources WA State Dept of Health; Office of Financial Management

What is it?

The United States is experiencing an epidemic of drug overdose deaths, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Since 2002, the rate of overdose deaths across the nation has increased by 79 percent. Since 2000, deaths involving opioids have increased 200 percent.

Opioids are narcotics that produce morphine-like effects used for pain relief and anesthesia. They also affect the areas of the brain that control breathing. High doses, especially of fentanyl, can cause breathing to stop completely. Fentanyl is a powerful synthetic opioid similar to morphine but 50 to 100 times stronger.

Heroin is a type of opioid made from morphine, a natural substance that comes from opium poppy plants. Prescription pain relievers and heroin are chemically similar and produce similar effects. Some people who get addicted to opioid pain relievers switch to heroin because it’s cheaper and easier to get.

How did it start?

According to the Washington state attorney general’s office, painkillers such as OxyContin and Vicodin became popular in the 1990s in the belief there was little or no risk of addiction based on allegedly flawed or even falsified research and marketing. Treating pain became easier and a higher priority. As the number of prescriptions increased, so did rates of abuse, addiction and overdose.

Opioid prescriptions and related overdoses fell in Washington after 2011 when the Legislature and health care providers began to crack down and encourage use of non-opioid painkillers. But users turned to heroin, fentanyl, methamphetamines and benzodiazepine (an anti-anxiety medicine), and cheaper synthetic opioids, including imitation fentanyl, and overdose rates for those drugs increased, according to the state Department of Health.

Locally, pills called Mexi-blues are counterfeit OxyContin tablets laced with fentanyl or other synthetic opioids that cost about $30 each, according to the Pierce County Sheriff’s Department. The same drug can be taken orally, snorted, smoked or injected. A single dose can be fatal.

How bad is it?

Though the number of total opioid overdoses has fluctuated since 2006, in 2016, 694 Washingtonians died of opioid-related overdoses, according to the health department. (2016 is the most recent year for which comprehensive data is available.)

From 2002 to 2004, the state death rate just from heroin was 0.65 per 100,000 residents; from 2014 to 2016 the rate was 4.12, an increase of 634 percent. In Pierce County during the same time periods the rate increased by 385 percent.

Sen. Patty Murray recently released a report showing that the cost of the opioid epidemic in this state in 2016 was $9.2 billion. The National Institutes of Health estimated that every dollar spent on treating addictions saves four to seven dollars in reduced drug-related crime and criminal justice costs. When savings related to health care are included, total savings can exceed costs 12 to 1.

How is it being stopped?

Drug addiction is increasingly recognized in the medical community as a medical diagnosis rather than a moral failing. The NIH website notes: “Addiction is defined as a chronic, relapsing disorder characterized by compulsive drug seeking, continued use despite harmful consequences, and long-lasting changes in the brain. It is considered both a complex brain disorder and a mental illness.”

Drug overdose deaths fell last year in 14 states including Washington, according to the CDC, where aggressive approaches to addiction treatment have been implemented, including:

• Equipping first responders with Narcan (also known as naloxone), an opioid receptor antagonist that reverses overdose and restores normal respiration. • Free needle exchange for IV drug users that allows them to trade dirty needles for clean ones, preventing deaths related to H.I.V., hepatitis C and endocarditis. These programs can also help users sign up for Medicaid and connect them with addiction treatment. • Providing fentanyl test strips to check street drugs for the presence of various fentanyl analogues that can lead to overdoses. • Expanding Medicaid to pay for long-term outpatient and residential care to provide access to medication-assisted treatment with buprenorphine and methadone regardless of a patient’s ability to pay.

Some in law enforcement and legislatures oppose these approaches in the belief they enable drug use. A Pew Charitable Trusts research group analyzed state-by-state data in 2017 on drug imprisonment, drug use, overdoses and drug arrests and found no evidence that they affected one another. A 2018 study from Stanford University concluded that three measures—a 25 percent reduction in prescriptions, greater access to naloxone and expanded methadone treatment—could reduce overdose deaths by 6,000 over 10 years. Washington has expanded the number of people receiving treatment for opioid addiction, according to the Washington Health Care Authority. Medicaid patients tripled from 2013 to 2016, when 15,259 Washingtonians enrolled in a medication-assisted treatment program. Many Washington state agencies also distribute overdose kits with naloxone. Half a dozen states, including Washington (and entities like Pierce County) are suing pharmaceutical companies for damages.

UNDERWRITTEN BY THE FUND FOR NONPROFIT NEWS (NEWSMATCH) AT THE MIAMI FOUNDATION, THE ANGEL GUILD, ADVERTISERS, DONORS AND PEOPLE WHO SUPPORT INDEPENDENT, NONPROFIT LOCAL NEWS