The summer of 1895 was a busy and exciting time for Edmund G. Edrington of Vaughn.

Edrington, who had worked as a salesman for several oil companies in his native Pittsburgh, had moved to Washington with his wife for health reasons a few years earlier, eventually settling in the growing community on Vaughn Bay. That summer all the parts of an idea he and other budding entrepreneurs had been working on for a couple of years seemed to be coming together; it was time to form a company, raise the capital and make it happen.

At the time the most popular means of getting around Puget Sound were the countless privately owned steamers that together were known as the mosquito fleet. Cities, towns and smaller communities on the water were growing fast, and business crisscrossing the sound carrying freight, mail and passengers was brisk. The boats were not particularly fast, however; in 1891 the trip from Seattle to Olympia with a stop in Tacoma took five hours. Travel by rail took as long and was not as convenient or flexible, and arguably not as scenic.

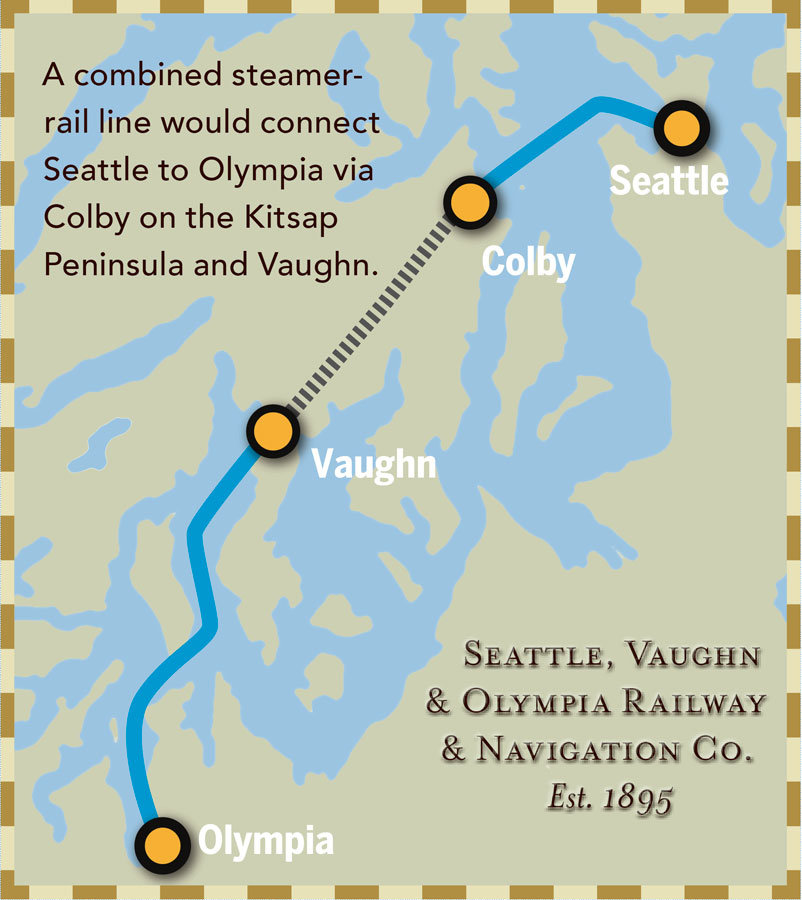

There had to be a better way, Edrington thought, at least for some of the popular routes, so in June of 1895 he announced the formation of the Seattle, Vaughn & Olympia Railway & Navigation Company. The new company planned to build, own and operate a combined rail-steamer line from Seattle to Olympia consisting of a fast steamer between Seattle and Colby in Kitsap County; a rail connection for the 12 or so miles between Colby and Vaughn; and a second fast boat directly from Vaughn to Olympia. Edrington claimed that the trip between Seattle and Olympia would be reduced to as much as one-third of the time it took using the water route and half of that on the rail route.

Edrington was the company’s president and general manager, and several Vaughn settlers whose names would become household words served as officers: Henry S. Coblentz was vice-president; George M. Robertson, secretary; R. W. Taynton, treasurer. Chester Van Slyke was listed as master mechanic. Reporting about a public meeting held in Vaughn on June 17, 1895, to launch the new company, the Seattle P-I wrote that “much enthusiasm was displayed. The right-of-way and much labor was (sic) pledged.”

The total cost of the railroad equipment alone was estimated to be $500,000, or about $15 million in 2021 dollars. Unnamed investors on the East Coast were interested in purchasing bonds in the company, Edrington said, but first they needed to see that the roadbed was graded and ties laid before they committed their investment dollars. The cost for that initial project was $30,000, or about $1 million today, with a projected completion date of January 1896. Edrington hoped that the citizens of the towns along the new line would come up with a large portion of that amount, presumably in the form of stock purchases. Seattle figured prominently on that list, and on July 3 the Seattle P-I reported that Edrington was to address the city’s Chamber of Commerce.

Edrington pulled out all the stops: The railroad, he argued, “will open up a rich country, where ultimately electricity may be used as a motive power, and the people are extremely anxious to receive the benefits of the road.” He added, “I consider that the building of this (rail)road will be of the greatest benefit to Seattle, as it will bring directly to this city all the business from the country about Olympia, as well as the great logging country about Shelton and back through Mason County.” The railroad would not sit idle when it was not used for the Colby-Vaughn runs: Edrington claimed that he had potential contracts in place to haul timber during those hours.

“Those who are interested in our company have been figuring on this enterprise for about three years,” Edrington told the Mason County Journal on July 5, “but the hard times prevented us from even attempting to get Eastern capital to take an interest in it.” The depression that had swept the country since the stock market crash of 1893 was about over, Edrington believed, so apparently those Eastern people of wealth were now in.

The company incorporated on August 17, 1895, with Edrington, Taynton and Robertson as incorporators, and with a declared capital on paper of $30,000.

After the announcement of its incorporation, however, the company was never heard from again. No reports in the press of a railroad from Colby to Vaughn or steamers connecting those points to Seattle and Olympia; no further mention of Edrington in the news.

By 1898 the Edringtons had moved back to Pittsburgh where Edmund once

again worked as a salesman, according to that city’s directory. Barely a trace of a memory of them remained in Vaughn; in her 1961 book “Parade of the Pioneers,” a history of Vaughn’s early days, Bertha Davidson wrote about the Edringtons that “they left as quietly as they had come.” She makes no mention of the company, even though the project had generated much enthusiasm, if the news coverage of the day is to be believed.

That is all we might have known about Edrington and the fast line from Seattle to Olympia had it not been for a recent serendipitous discovery of copies of Edrington’s letters in the archives of the Key Peninsula Historical Society, created using a letter-copying press, an early form of duplication before the widespread use of carbon paper. The set includes some 30 letters about the company, recording his urgent and at times desperate attempts to get bids for railroad equipment and the steamers from various manufacturers nationwide, and to raise the $30,000 capital needed. They also tell of disputes and disagreements with Taynton and Robertson, the other two incorporators, who apparently delayed filing the corporation papers with the state, unbeknownst to Edrington and much to his consternation.

The roadbed between Colby and Vaughn was never built. In a letter to Washington Secretary of State J. H. Price on Jan. 9, 1896, Edrington lays out the company’s difficulties and asks if he was required to file an annual report since, as he explained, “there has not been a single share of stock sold nor has any work been done for the company” except for his own administrative work.

Finally, on June 30, 1897, two years to the day since the company was first mentioned in the press, Edrington wrote to Taynton and Robertson letting them know that the corporation should be dissolved and asking them to pay their share of the required fees. That never happened; the company stayed on the books and was administratively dissolved in 1923, following the passage of a law that provided for that action for corporations that had not paid their annual license fee for over two years.

Edrington died in Pittsburgh in 1910 at age 56, still listed as a salesman. It was the dawn of a new century that would see enormous advances in transportation; the line to Seattle to Olympia via Vaughn might not have survived. But for a few weeks in the summer of 1895 Edrington’s world was full of possibility; there are probably a myriad of reasons why his vision was doomed to fail, but at least he had dared to dream.

UNDERWRITTEN BY THE FUND FOR NONPROFIT NEWS (NEWSMATCH) AT THE MIAMI FOUNDATION, THE ANGEL GUILD, ADVERTISERS, DONORS AND PEOPLE WHO SUPPORT INDEPENDENT, NONPROFIT LOCAL NEWS