United States Penitentiary, McNeil Island, photographic print, cyanotype. Buildings of the U.S. Penitentiary on McNeil Island, WA, circa 1890-91. Looking out over Tacoma Narrows. Washington State Historical Society, Springer Family Collection, C2014.165.1.

United States Penitentiary, McNeil Island, photographic print, cyanotype. Buildings of the U.S. Penitentiary on McNeil Island, WA, circa 1890-91. Looking out over Tacoma Narrows. Washington State Historical Society, Springer Family Collection, C2014.165.1.

Our neighboring prison island has a complicated past and uncertain future.

McNeil Island has a storied and complicated past, and its largely forgotten history is the subject of a major exhibition at the Washington State History Museum in Tacoma that runs until May 26.

Situated in Carr Inlet between Fox and Anderson islands and less than half a mile from the Key Peninsula, McNeil Island is currently home to Washington’s Special Commitment Center, a facility operated by the Department of Social and Health Services providing treatment to persons designated as sexually violent predators following the completion of their prison sentences.

The island is best known, however, as the site of a series of prisons from 1875 to 2011. It is the only prison in the U.S. to have served under three jurisdictions: territorial, federal and state. It housed the Washington Territorial Penitentiary from 1875 to 1889; a federal penitentiary from 1889 to 1981; and a state prison from 1981 to 2011.

The federal government bought the land for the territorial penitentiary prison from Jay Emmons Smith, an island settler, in 1870. The 27.27-acre parcel was located in a bay at the southeast end of the island facing Steilacoom, with majestic views of the Sound and Mount Rainier.

First settled in the 1850s, the island was home to a small community for several decades. It included a school, church, cemetery and post office. Many residents would later work at the prison.

By 1936, however, the federal government had acquired all the privately owned land on the island and the residents had moved out; prison staff in later years lived in government-owned housing. In 1937, the government exhumed the 86 bodies from the island cemetery for reburial elsewhere, since the island was no longer open to the public.

Construction of the territorial penitentiary was completed in 1875. The first three prisoners, two men convicted of selling liquor to Indians and one for robbing a store in Fort Walla Walla, arrived on May 28, 1875 accompanied by a U.S. Marshal.

The prison’s design reflected changed views on incarceration, stressing rehabilitation and eventual reintegration into society rather than isolation and retribution. Prisoners lived together in communal cell houses, two to a cell, which they were later allowed to decorate,

Work provided an important pathway to rehabilitation. There was no hard labor at McNeil; reform-minded wardens allowed all work to be voluntary. Prisoners soon discovered that working was preferable to spending the day in their cells and allowed them to participate in the prison’s recreational opportunities.

Prisoners worked in the kitchen, vegetable garden, grain fields, dairy and pig farm, slaughterhouse and chicken farm. The Honor Farm, created in 1926, housed 200 trusted inmates and was later used by the state prison for its Work Ethic Program.

Inmates also cleared land as needed and maintained the prison’s infrastructure using their existing skills or learning new ones in preparation for their eventual release. There were carpentry, metalsmithing and boatbuilding shops; a tailor shop; a brickyard; an acetylene-gas plant and later an electrical plant; water works, sewer and sanitation facilities and a hospital; all provided work and training opportunities and made the prison largely self-sufficient.

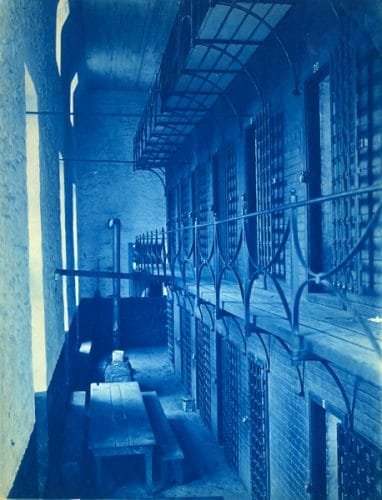

In addition to work there were educational and recreational opportunities: night school, a library, music, movies, basketball, baseball and more. United States Penitentiary, McNeil Island, Photographic print, cyanotype, circa 1890-1891. Interior of a cell block at the U.S. Penitentiary on McNeil Island, WA. Washington State Historical Society, Springer Family Collection, C2014.165.3.

United States Penitentiary, McNeil Island, Photographic print, cyanotype, circa 1890-1891. Interior of a cell block at the U.S. Penitentiary on McNeil Island, WA. Washington State Historical Society, Springer Family Collection, C2014.165.3.

The prison’s population steadily increased over the years and new cell houses were built to meet the demand. In 1894, McNeil housed 58 inmates; by 1925 that number had grown to 596, and that year the prison could accommodate as many as 1,000 prisoners.

The increase in the rate of incarceration reflected in part general population growth, but was also the result of shifting societal and cultural norms that in turn affected the types of crimes committed and prosecuted.

In the prison’s first decades, 30 percent of the inmates served time for selling alcohol to Indians; others had been convicted of sending obscene material by mail or were smugglers and counterfeiters. Criminals convicted of violent acts were rare; in 1909 Robert Stroud, who gained notoriety in later years as the Birdman of Alcatraz, pleaded guilty to manslaughter and served the first three years of a 12-year sentence at McNeil before he was transferred to Leavenworth.

Convictions for draft evasion and dereliction of duty predominated once the United States entered World War I in 1917. The passage of Prohibition in 1918 saw an increase in tax evasion and gang-related crimes involving the sale of alcohol across state lines.

Suspected illegal immigrants were also detained at McNeil and processed prior to deportation. The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 and successor legislation in effect until the 1920s resulted in the detention and subsequent deportation of thousands of Chinese immigrants, many of whom went through McNeil.

War- and drug-related offenses and violent acts increased the inmate population in the 1960s; by 1966 McNeil housed 1,340 inmates. Prison gangs changed prisons even further in the 1970s.

In spite of the relatively benevolent environment at the minimum- to medium-security prison, there were countless escape attempts over the years, most of them ending with capture. Many who escaped by swimming across Pitt Passage were helped in later years by Longbranch resident Anna Peyser (known locally as Driftwood Annie), who lived above the beach across from the island. Peyser offered escaped prisoners a hot cup of coffee and warm clothing and sent them on their way, to the frustration of McNeil wardens. Peyser died at 95 in 1984.

McNeil Island had been run in an exemplary manner as a federal prison for over a century, even serving as a model and training ground for the U.S. Penitentiary at Alcatraz, which opened in 1930. In the late 1970s, however, the federal government decided to close the prison because of an unfavorable Government Accounting Office report, the obsolescence of the prison and the trend towards smaller prisons. The last federal prisoners were moved off the island in March 1981.

But that was not to be the end of McNeil Island’s use as a prison. In 1981, Washington State leased the site for a new state prison. The new McNeil Island Corrections Center occupied 66 of the island’s 4,413 acres; the remaining land was designated as a wildlife reserve.

In 1984, in an agreement negotiated by Washington’s congressional delegation, the U.S. gave the island to the state.

Citing the need for budget cuts, the state closed the prison in 2011. Prisoners were moved and the prison was effectively abandoned.

The Special Commitment Center is the only facility still operating on the island, indefinitely housing and treating 218 convicted sex offenders as of June 2018 in a location separate from the prison grounds. Their indefinite confinement is a result of a 1990 state law mandating sex offenders deemed likely to reoffend be involuntarily committed after serving their prison sentences.

The commitment center has become increasingly expensive to operate since the prison closed as it cares for an aging population and is responsible for all of the island infrastructure. There is increasing interest from state legislators and elsewhere to find a more efficient solution on the mainland.

The rest of the island is now the McNeil Island Wildlife Reserve Unit, managed by the Department of Fish and Wildlife. The public is not allowed on the island.

See also New Exhibit Explores McNeil Island, KP News, March 2019.

UNDERWRITTEN BY THE FUND FOR NONPROFIT NEWS (NEWSMATCH) AT THE MIAMI FOUNDATION, THE ANGEL GUILD, ADVERTISERS, DONORS AND PEOPLE WHO SUPPORT INDEPENDENT, NONPROFIT LOCAL NEWS