Some dirty comic book about the Holocaust got banned from the eighth grade English Language Arts curriculum by the McMinn County School Board in southeast Tennessee Jan. 10, because the book has cuss words and nudie drawings.

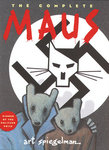

We’re talking about Art Spiegelman’s 1986 graphic memoir “Maus,” a landmark work of comic art which, as a college humanities professor, I have taught several times and expect to teach again.

“Maus” holds a canonical place in comics history, autobiography and Jewish Studies. It remains the one work of graphic narrative to earn a Pulitzer Prize (in 1992). As recently as 2009, the Young Adult Library Association named it an Outstanding Book for the College Bound and Lifelong Learners, and in 2020 the New York Public Library voted “Maus” one of the 125 most important books of the last 125 years.

Spiegelman’s opus deserves every accolade it gets, because without exaggeration we can say that it redefined the possibilities for graphic narrative, bringing whole new audiences to this art form, showing it can excel at addressing the heaviest, weightiest, most daunting of subjects. It proved that — despite the name — comics don’t have to be funny (though “Maus” often is).

“Maus” tells the story of one Jewish Holocaust survivor’s experiences in Poland and the death camps, as told by the survivor, Vladek Spiegelman, to his son Art. But the story’s transformation into a work of graphic narrative alters the stakes in fundamental ways, first through what seems like an overly obvious visual metaphor: Spiegelman draws the Jews as anthropomorphized mice, the Germans as cats, the Poles as pigs, and so on. Secondly, Spiegelman utilizes the language of comics to explore the minutest details of Vladek’s experience, down to the way he repaired footwear in Auschwitz — making himself indispensable to the people who held his life in their hands. Indeed, “Maus” makes astonishingly vivid what day-to-day life in the camps was like: the terror, yes, and the anxiety, but also the boredom, the denial, the disorientation, the back-stabbing, the banality.

Things get more serious when discrepancies emerge between Vladek’s personal memories of the Holocaust and the historical record. The two get into a debate about whether an orchestra was playing at the entrance to a death camp as prisoners marched out the gate (as documented by scholars). Vladek says there was no orchestra — after all, he was there, and he would have noticed. Nevertheless, over two succeeding panels, Spiegelman shows camp prisoners indeed marching to an orchestra — overriding his father’s testimony. It’s hard not to see such scenes over disputed facts as Oedipal one-upmanship on Artie’s part; as the memoirist, he always wins.

Except when he doesn’t. Part I of “Maus” ends with an excruciating episode when Vladek admits to burning Anja’s diaries after her death by suicide. Artie had been trying to locate them to piece together his mother’s later years and her feelings about him. Vladek brutally takes that chance away from him. “God damn you! You — you murderer!” Artie yells. “How the hell could you do such a thing!!”

This is one of the scenes highlighted by McMinn School Board member Mike Cochran, who said at the Jan. 10 hearing “A lot of the cussing had to do with the son cussing out the father, so I don’t really know how that teaches our kids any kind of ethical stuff. It’s just the opposite, instead of treating his father with some kind of respect, he treated his father like he was the victim.” I read the whole hearing transcript, and all the board’s arguments for removing the book reflect this kind of blinders-on, context-free, willful misreading.

The charge of supposedly salacious naked drawings? They seem to mean a panel (above) where we see Anja’s body in the bathtub after her suicide. Spiegelman himself seemed mortified by that characterization. “As offensive as those parents seem to have found my book, I found the description of my dead mother’s body in a bathtub where she had slashed her wrists described as a ‘nude woman’ deeply troubling to me,” he told a Feb. 7 online forum organized by the Jewish Federation of Greater Chattanooga. “It was hard to draw, it was hard to think about. I wasn’t present in the moment she was discovered … I would say a ‘naked corpse’ would probably be a more intelligent use of language.”

Reading about the Spiegelman family’s modern-day travails and dysfunction taught me that the Holocaust was not an event confined to the past, but one that continued to live on in its survivors and their children and their children’s children long after the war, right up to the present. The unique immediacy of comics brought that devastating truth home like no other medium could.

In the meeting transcript, I found the testimony of Steven Brady, an instructional supervisor who tried to talk the board out of its precipitate and wrong-headed decision, especially poignant. Let him have the final word:

“Every lesson we teach gives us a chance to make a change for the better for our students … I appreciate the stand that you all are taking to assure the public that we care about our kids, and we believe it’s important to teach our students the difference between right and wrong and help them be ethical people with compassion and morals with respect for others.

“There are many lessons that can be learned through this book about how we treat others, how we speak, things that we say, how we act and how to persevere.”

UNDERWRITTEN BY THE FUND FOR NONPROFIT NEWS (NEWSMATCH) AT THE MIAMI FOUNDATION, THE ANGEL GUILD, ADVERTISERS, DONORS AND PEOPLE WHO SUPPORT INDEPENDENT, NONPROFIT LOCAL NEWS